Sixty-seven percent of the world’s 42.6 million refugees live in neighboring countries. That’s the case for most of the 192,000 people living in the Rhino Camp Refugee Settlement in northwestern Uganda. The vast majority—85 percent—are women and children. They come from across the region: from the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Sudan, Rwanda, and Burundi.

Displaced from their countries of origin primarily by conflict, Rhino Camp is one of the largest refugee settlements in the region. Its population already outnumbers the host community’s population of 126,000 residents, and is expected to continue growing in the months ahead. For most of the residents, the hope is to build a new life in Uganda, rather than to return home.

That means schools for children, jobs for adults, and healthcare and basic services for everyone. But the settlement’s vast geography has limited infrastructure: there is no electricity grid, with most energy generated from solar power. The nearest town, Arua, is a two-hour drive away along uneven, sandy roads. Without widespread broadband or fiber, Internet connectivity is patchy, slow, expensive, and primarily mobile. Which puts access to education, healthcare, and sustainable livelihoods even farther out of reach.

The situation is further complicated by humanitarian funding cuts and the need for financial self-reliance. That’s why the Internet Society partnered with the Community Empowerment & Transformation Agency (CETA) to train Rhino residents on how to bring connectivity to their community, and to ensure that the refugees themselves have the skills necessary to build and use the Internet without long-term dependence on international aid.

“There are limited jobs in the Camp. Refugees are not exposed to many job opportunities, especially as there is no Internet. Most of the jobs are online and though we have the skills, we lack the Internet to look for jobs and market our produce,” said Samuel Lasu, co-founder and executive director of CETA.

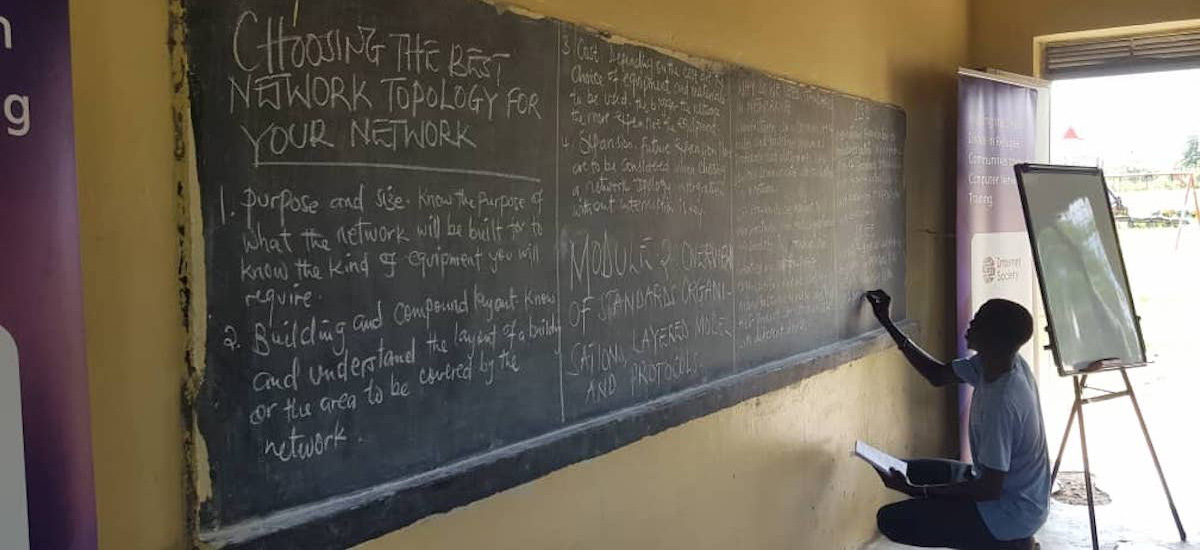

Organizing the trainings posed some notable challenges, as it was important to train instructors who understood the local context and day-to-day challenges of the settlement. Asking people to travel two hours, one way, to conduct a training is also not realistic, or sustainable. Hardware shortages also created hurdles: there were no computers. The first cohort learned with just a blackboard, printed materials, and a pad and pen for note taking.

Thankfully, organizers were able to work through these challenges. To address the need for local instructors, they invited Ruth Njeri to train five Rhino Camp residents to become trainers themselves. Njeri took a course in 2022, co-facilitated by the Internet Society Kenya Chapter. Since then, she has passed on her expertise in designing and deploying computer networks by training others to run similar courses. “To have trainers who live in the community made a huge difference in how many courses we could deliver,” said Joyce Dogniez, vice president of empowerment and outreach with the Internet Society Foundation.

The first three cohorts, a total of 135 learners, graduated in October, and celebrated with a parade, helping spread the word about the course to others. With so many now equipped with knowledge about how to deploy computer networks, Hello World, an Internet Society Foundation grantee, was invited to identify a connectivity solution for the camp. After an extensive stakeholder consultation, they proposed a community-centered connectivity pilot in partnership with RENUMESH, a solar-powered router manufacturer. The pilot broke ground on 6 December on two hubs that will give Rhino Camp residents access to affordable, reliable Internet.

Many of the graduates have applied what they’ve learned into their work life already, despite the lack of widespread Internet. Lydia Nabintu was among the first 45 Rhino learners to take a course on how to design and deploy computer networks. Originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lydia had limited information and communication technology (ICT) experience. Through hands-on training with CETA tutors, she learned the fundamentals of computer networking, how to set up and manage small Wi-Fi networks, and basic online safety and cybersecurity skills.

“Before this training, I only knew how to use a phone for calls and WhatsApp. Now, I can design and connect a small computer network for a school or office. I never imagined I could understand how the Internet actually works. This knowledge has given me confidence and a new career path. I want to help my community connect to the world,” said Lydia, who is now leading a local church, supporting members with ICT troubleshooting, and helping fellow youth understand digital tools. Her dream is to become a certified network engineer and train more girls in her community.

Peace Muna Peter, a tailor who runs her own business, also found the course to be a game changer. “I have a small tailoring shop at home, the course opened my eyes to how the Internet can grow my skills and business,” she said. Previously, she managed customer records manually, and the limited connectivity at the camp made it impossible for her to expand her business. Through the course, she learned how networks operate, how to connect her phone to a hotspot, and how to troubleshoot connectivity challenges. “Now I can showcase my work online and access new opportunities I never imagined before.”

What the learning ecosystem at Rhino lacks in resources, it makes up for in terms of strategy: by training locals on the ground to establish Internet connectivity through community networks, and by expanding the instructor base, the community is poised to see dramatic advances toward connectivity in the months and years ahead.

Michuki Mwangi, distinguished technologist for Internet growth at the Internet Society, highlights the importance of innovative solutions to achieve universal connectivity: “Experiences like these show that meaningful connectivity grows strongest when it is built from the ground up. Community-driven solutions—rooted in local values, knowledge, and leadership—are essential to reaching universal connectivity. When marginalized communities are empowered to design, build, and sustain their own networks, they become more resilient, more connected, and better equipped to shape their own digital futures.”

If you’d like to support projects such as Rhino, or learn more about how we are helping connect communities, you can learn more about our work.

Image © Samuel Lasu