Sometimes you need to go back to the past to learn lessons for the future, and with much current discussion revolving around the transition from IPv4 to IPv6, we should perhaps reflect that we’ve been here before when the Internet transitioned from NCP to the TCP/IP protocols. That’s why it was great to have a presentation on the ARPANET TCP/IP migration of 1983 from Ron Broersma (SPAWAR-US Navy) during the recent NLNOG Day in Amsterdam.

Ron joined the US Naval Undersea Center in 1976 where his responsibilities included operating Node #3 of the US Department of Defense ARPANET, which was comprised of a number of nationally connected (usually at 50 Kb/s) mainframe systems that eventually evolved into the Internet. An IMP (Interface Message Processor) at each node ran the NCP (Network Control Program) protocol that performed the routing functionality, and were identified with an 8-bit address. This allowed for a total of 256 hosts; split into 2 bits for the host (for a maximum of 4 hosts per node), and 6 bits for the network (for a maximum of 64 nodes). Addresses were denoted with a / as a separator, which meant Ron’s node was addressed as 0/3.

The ARPANET was designed in an era before microcomputers which only arrived in the mid-1970s, before which computing facilities required substantial investment and therefore need to be shared. However, even then it was becoming clear that just 256 addresses would impose an intolerable limitation on expansion of the ARPANET, which had even branched out internationally to University College London (UCL) in the UK. The solution of course, was to develop a new protocol that would increase the address space, which probably sounds familiar to regular readers of the Deploy360 blog!

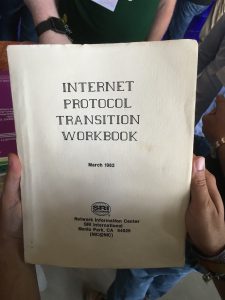

Thus TCP/IP was born, although several different prototypes were actually developed and tested between 1975 and 1982 before the final specification was settled upon. In March 1982, the US DoD declared TCP/IP to be its official standard, and a transition plan outlined for its deployment by 1 January 1983. Both protocols would be supported until then, but after that NCP would be turned off and any hosts not making the transition would lose access to the ARPANET!

The immediate impact of TCP/IP adoption was a huge increase in the available address space, as 32 bits allows for approximately 4 billion hosts. Unfortunately, this address space was not allocated efficiently due to router limitations and the way existing NCP addresses were transitioned. For example, Ron’s network became the Class A address 10.0.0.3 with 16 million possible hosts, which even accounting for the growth in the Internet, proved to be far more than necessary and was eventually returned to IANA.

However, another consequence was that hosts no longer needed to be directly connected to an IMP, which allowed a network of networks to be built, exterior routing protocols to be run, and essentially created the Internet as we know it today.

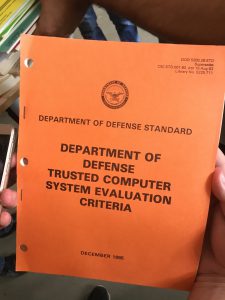

With far more systems connecting to the Internet, another issue arose with respect to keeping track of how to access these. Host names were originally mapped to addresses in a downloadable file called HOSTS.TXT that was compiled by the Stanford Research Institute. Name conflicts arose though, and it became too much effort to maintain this file, which led to the development of the Domain Name System in 1983. It’s perhaps also worth pointing out that the first hacking incident occurred that year too, which meant system and eventually network security needed to be considered and which led to the development of the Orange Book standard.

The ARPANET’s research functions were eventually taken over by the US National Science Foundation-funded NSFNET, with its military role being taken over by the separate MILNET. It survived until 1990 when it was dismantled, with just a few artefacts remaining as testament to its pioneering role in the evolution of the Internet.

Perhaps the one lesson to learn though, is that protocol transition can happen if there’s a strong incentive such as being disconnected. This happened before with the move to IPv4, and it can happen again with IPv6!

We at Deploy360 like to do our bit to help, so please take a look at our Start Here page to understand how you can get started with IPv6.